When I was in the first year of my Ph.D. program in theology at the University of Dayton, I was blessed with an opportunity to write about the Brethren in Christ for a seminar focused on historiographical issues in relation to theology. I chose to explore what role certain works of historical recovery may have had on the denomination’s decision, first made in 1982, to “affirm the ministry of women in the life and programs of the church” (General Conference Minutes, 1982). Here’s a summary of some of what I found.

Early Female Faith Leaders

The names and stories of certain women are now well-known to those of us with a strong attachment to the Brethren in Christ and an appreciation for our focus on missions and outreach. Rhoda Lee is one such name. She galvanized the church over a two-year period with speeches read before General Conference (at a time when General Conference was an all-male body) and with passionate and well-reasoned arguments in the Evangelical Visitor (the denomination’s regular publication for many years).

Another such name is Frances Davidson. She was the first Brethren in Christ person to gain a master’s degree, a key leader (probably the key leader) on the first BIC missions team sent to Africa, a missionary memoirist, and an educator.

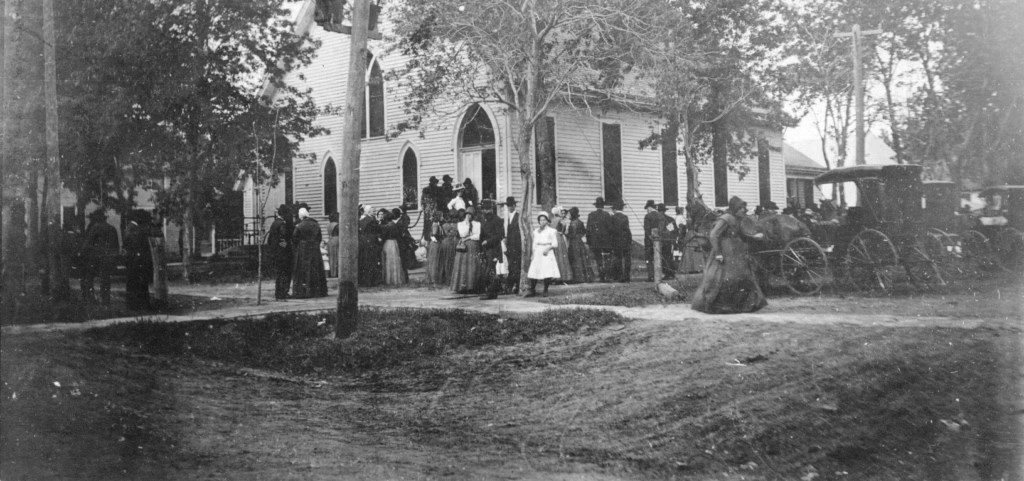

These two women are perhaps the most famous members of a much wider cohort of women leaders from that earlier, crucial era in our history. That cohort includes many others, such as Sarah Bert, Mary J. Long, Effie Rohrer, and Anna Kraybill. Some of these women were preachers who addressed both men and women with the word of God. All of them were highly influential, exercising godly authority and oversight over important ministries. And all of them were doing these remarkable things 100 or more years ago. While we know their names now, however, their names were not so well remembered in the middle of the last century.

Brushed Under the Rug

The minutes of General Conference from 1894, for instance, do not mention Rhoda Lee. They do record the action of Jacob Stauffer offering the first $5.00 for missions work, but fail to mention that he gave in response to Rhoda Lee’s call and that she began passing a hat through the assembled body to collect funds for the work. This failure of the record is a token of a larger failure. Though never entirely forgotten, the memory of Rhoda Lee (and of many of these women) faded from the shared consciousness of the denomination in the years following their pioneering leadership. They were not, in later decades, usually included as key parts of the story of our church as we regularly told it.

For example, the story of the missions movement within the Brethren in Christ was summarized from the podium of the 1978 General Conference without reference to either Rhoda Lee or Frances Davidson. A speech on missions at that meeting briefly recalled the earliest era in missions by referencing two things: Stauffer’s $5.00 at the 1894 conference and Jesse Engle as the first missionary to go abroad. Engle was a wonderful and brave man; he was also the only man on the team of five people that first went abroad. He was accompanied by his wife and three other dedicated women, including Frances Davidson whose sharp mind, indomitable spirit, administrative acumen, and eloquence made her the most dynamic member of that missions team.

Embraced and Upheld

So what changed? We could not now offer even a brief summary of the early missions effort without mention of these women. Why? During the 1970s, a growing number of people within our denomination became increasingly convinced that we were ignoring biblical wisdom and the prompting of the Spirit by denying women opportunities to minister in credentialed roles. By 1978 the denomination had formed a Committee on Women and Pastoral Ministry to investigate these matters and make recommendations back to the General Church.

1978 was a watershed year for Brethren in Christ historiography. In 1978 Carlton O. Wittlinger published Quest for Piety and Obedience (the now standard history of our church), E. Morris Sider published Nine Portraits (a collection of nine biographies of key people including Frances Davidson and Sarah Bert, and Sider, Wittlinger), and several others founded Brethren in Christ History and Life, our denomination’s still-running historical periodical. Quest for Piety and Obedience accurately foregrounded the role which so many women had in leading the denomination into missions work. Nine Portraits showed two women in ministry whose work at least equaled that of any male minister. And between 1978 and 1982, no less than four pieces of biography, written by four women about four other women in ministry from that earlier era were published in Brethren in Christ History and Life.

Thus, in the four years leading up to our embrace of women in ministry, a remarkable transformation of our historical consciousness was effected. The decision of General Conference in 1982 gives several reasons for itself. The final one notes “the service and leadership of the sisters, in both the past and the present” as justification for ordaining women. Jesus said that you can tell a true prophet from a false one by the fruits they produce. We had long cherished the fruit of our first missionary endeavors at the turn of the previous century. When we were reminded in the late 1970s and early 1980s that this fruit came, to a large degree, from the ministry of women, we could no longer deny that God calls sisters, as well as brothers, into roles of ecclesial leadership.

Originally published for the Spring 2018 issue of Shalom! A Journal for the Practice of Reconciliation.